Australia is steadily working towards data systems that will enable greater understanding of interactions between human, animal and ecosystem health and their relationship to AMR and antimicrobial use.

Compared to many other nations, Australia already has a strong data network and surveillance around AMR and antimicrobial use in humans, according to Christina Bareja, Director of Antimicrobial Resistance Policy Section for the Interim Australian Centre for Disease Control.

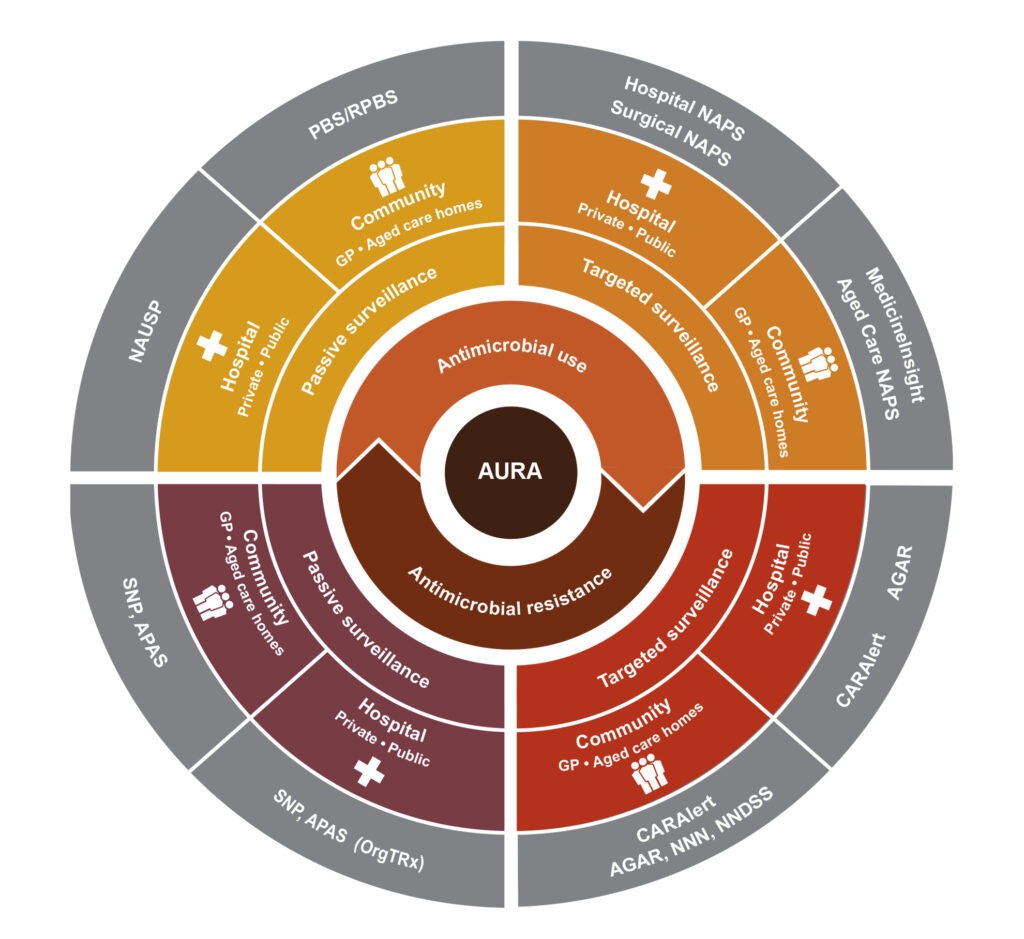

For example, a comprehensive report called AURA has been issued every two years for the past 10 years, detailing patterns and trends in antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in acute and community healthcare settings.

Ms Bareja says that in the future, AURA could become more dynamic, with real-time dashboards. “The challenge is giving the people who can actually make a difference and address AMR data in the most dynamic and interactive way so that it really informs their actions and empowers them to make informed decisions,” she says.

This could include a greater ability for clinicians, such as GPs, to understand resistance in their local area. “It’s important to have access to timely data to inform their antibiotic prescribing with relative confidence that it will work because of what’s in circulation around the community,” Ms Bareja says.

AURA = Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Australia; CARAlert = National Alert System for Critical Antimicrobial Resistances;

GP = general practice; NAPS = National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey; NAUSP = National Antimicrobial Utilisation Surveillance Program;

NNDSS = National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System; NNN = National Neisseria Network; PBS = Pharmaceutical Benefits

Scheme; RPBS = Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme; SNP = Sullivan Nicolaides Pathology

Finding the gaps

Ms Bareja says that data about antimicrobial use and prescribing is very nuanced, and there are gaps that need to be filled. “In primary healthcare, we can get data through the PBS, but antimicrobials aren’t always prescribed on the PBS,” she says. “They can be prescribed through a private script. So, it’s understanding where our gaps are and then trying to collaborate to fill those gaps.”

“

You can actually end up with really quite erroneous conclusions, or you can end up damaging relationships with people so that they don’t want to interact with you in the future.

It’s a challenging piece because it hasn’t been done before.

Christina Bareja

Technology will increasingly make participation in data collection more seamless, and help create a more holistic view of antimicrobial resistance in Australia, bringing human health together with animal welfare, agriculture and the environment. “That’s a piece that we’ve been working on for a while,” Ms Bareja says. “It’s a challenging piece because it hasn’t been done before.”

Rachel Iglesias leads the One Health team in the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, addressing the links and interdependencies between human, animal and ecosystem health. She says there is plenty of data available to help mitigate AMR across these areas, but it is incomplete and not well organised. “It’s not necessarily all in the one place, so there’s not a single point of truth that you can go to for everything that you might want data-wise,” she says.

“I’d really love to have good data on how people in Australia who prescribe antimicrobials for animals are actually prescribing them. What are they prescribing for? Is that use appropriate? How much is being used? What animals is it being used in?

“Some of that exists, some of it could be captured with the right sort of intermediate software. But the people – the prescribers who are responsible for that data – aren’t ready for that yet.”

People are the key to data

Ms Iglesias says those prescribing these drugs are key to gaining more data on antimicrobial use. “The people are the most interesting part of the system,” she says. “It’s really important to understand their context, their concerns, their limitations, because all of that impacts on how much they’re prepared to give you in terms of data and how much they can help you interpret that data.”

For example, challenges when monitoring and reporting antimicrobial use in animals may include commercial confidentiality in terms of the pharmaceutical industry, and a fear from livestock industries that the information will be used against them.

“If you’re not conscious of all of those other things, you can actually end up with really quite erroneous conclusions, or you can end up damaging relationships with people so that they don’t want to interact with you in the future,” Ms Iglesias says. “So, at the moment, we’re looking at how we can start doing more public reporting of data like that in a way that’s safe for all of the industry participants. And as they start to see that it is safe, the hope is that we’ll be able to do more of it.”

“

Our responsibility is to try to keep the focus on AMR enough so that work keeps happening.

Rachael Iglesias

She says that over time, data will be used to help solve complex questions about the interconnectedness between animal and human health. “How do the bacteria end up from potentially the gut of an animal that’s been treated with antimicrobials through to a human who’s got an infection? That is a really complex question to understand and unpack, and I think data will help with those complex, system-level issues that we’re still coming to terms with.”

However, to do so, AMR needs to remain a priority to the public and policy makers. “One of the challenges with antimicrobial resistance is it’s a crisis that’s unfolding very slowly, unlike COVID-19, for example,” Ms Iglesias says.

“Our responsibility is to try to keep the focus on AMR enough so that work keeps happening. Certainly, I’d like to hope that over the next 5 to 10 years we can get some real progress on antimicrobial use monitoring in animals in Australia.”

Ken Eastwood is a highly experienced, award-winning editor, journalist, author and communicator, with particular expertise in science, agriculture, sustainability and rural affairs.